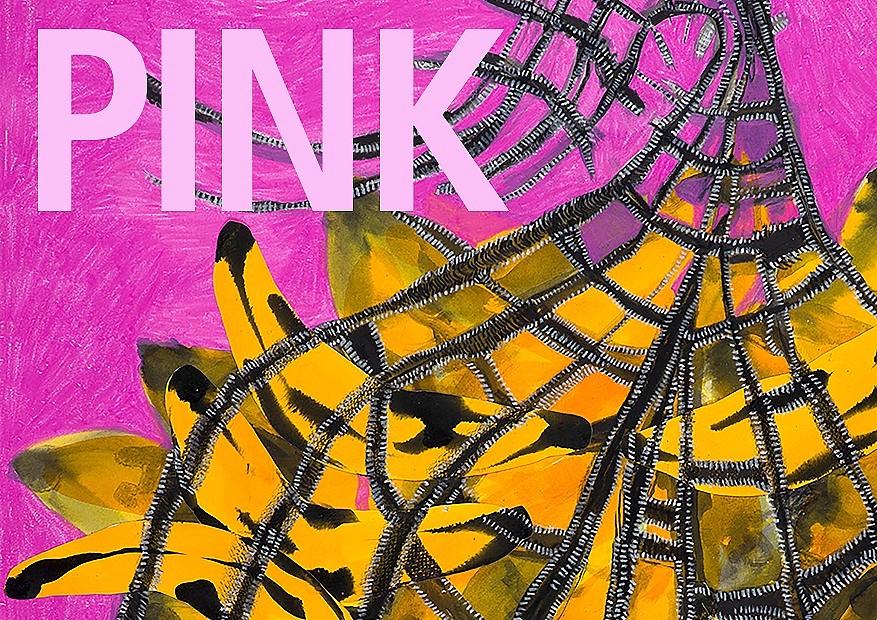

PRESS RELEASE

PINK: Art Joburg Group Exhibition

Nov 6 – Nov 18, 2020

PINK

The colour of candy-floss, flamingos, blossoms and lipgloss.

The colour of almost every toy in the “Girls” section of our stores.

The colour of optimism, rose-tinted glasses and innocence.

The colour of internal flesh.

The colour of protest.

Pink is powerful.

There is so much to say about the colour pink; it is a colour, a feeling, a sound, a memory.

It’s origin as a word in the English language is linked to the history of fabric dye, as pink cloth became available for the first time in the 14th century. In other languages it refers to the presence of the colour in nature, predominantly in flowers - hence the French word for pink, ‘rose'. There is no naturally occurring pink pigment, so artists and artisans have, over centuries, had to mix red and white to achieve the colour in paintings, ceramics and textiles.

Its history in fashion is complex, and gendered.

The colour was hugely popular in 18th century France during the Rococo period, with men and women donning pink outfits in the courts of Louis XV. In the 19th century, pink became a gendered colour, but not as one would expect. In fact, it was boys who were dressed in shades of red, pink and white whilst girls wore blue as it was considered a more delicate colour and thus better suited to ‘the fairer sex’. This standard then reversed in the 20th century, coinciding with the rise of capitalism, and department stores began to advertise pastel shades of pink as feminine colours, and shades of blue for men.

In 1937, Italian fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli made “Shocking Pink” her signature colour; the bright intensity of the colour rebelled against the demure, washed-out pinks popular in women’s fashion, as Schiaparelli pushed back against the notions of female fragility through her bold colour and avant-garde designs.

The association of the colour pink with femininity was so well established that, during the Second World War, the Nazi’s forced gay men in concentration camps to wear a badge of a downward-pointing pink triangle; the association of pink with the female sex was used as a weapon to publicly humiliate men by challenging their masculinity. In the 1970s, gay rights activists appropriated this symbol, intended to cause shame, as a symbol of pride and liberation.

The weaponisation of the colour pink by men, against men is a reoccurring theme in our history.

In 1979, Alexander Schauss conducted multiple studies on the psychological effects of the colour pink. He conducted an experiment in an all-male Naval correctional institute in Seattle, Washington, and painted some of the confinement cells a specific shade of pink (he termed the shade “Baker-Miller Pink”). After monitoring the behaviour of the prisoners, Schauss found that the colour soothed and calmed inmates thus decreasing the incidents of violence. Subsequent studies have shown that although the colour seems to lower the incidence of aggressions by prisoners at first, it may also cause higher levels of aggression of exposure over time. Kevin Bideaux in “Rethinking Baker-Miller Pink through gender studies”, suggests that the reason behind this phenomenon may be the perceived emasculation of male inmates by creating a feminine environment, devoid of symbols of masculinity and positioning them in a “feminine” position of subjugation by the hyper-masculine dominance of the prison system.

Currently, there is a global movement by women to weaponise the colour pink in order to combat gender-based violence and fight for women’s rights.

In 2019, the ‘Pink Chaddi Protest’ was organised on Facebook by a group called the Consortium of Pub-going, Loose and Forward Women.

The protest was a reaction to a right-wing political party, the Sri Ram Sena, who campaigned to ban women from pubs and bars in order to protect women from “immoral behaviour”, such as drunkenness and promiscuity. This moral-policing of women’s behaviour by men caused outrage amongst Indian women and in response, the Consortium of Pub-going, Loose and Forward Women called on Indian women to send pink chaddis (panties) to the Sri Ram Sena. By sending such intimate garments, in the highly-feminine colour pink, to a public, political (and very masculine) space, these women asserted their right to inhabit public spaces and express their sexuality without being shamed or shunned.

The ‘Gulabi Gang’ are also based in India, and are a group of women who dress in vivid pink sarees and campaign against gender-based violence, often wielding sticks in order to deter and punish perpetrators of domestic and sexual abuse.

In 2017 The Pussyhat Project was started in America, specifically for the Women's March which took place the day after the inauguration of President Donald Trump that year. The project encouraged women to knit, sew or craft pink hats with cat-like ears, a play on the word “pussy” - a reference to President Trump’s infamous 2005 remark regarding women, "grab them by the pussy." The wearing of these hats en-masse demonstrated the enormous impact of this remark on the American public – it also served as a symbol of retaliation and defiance of the red MAGA hats worn by Trump supporters. The pink Pussyhats demonstrated a collective rejection of sexism, and utilised feminized crafts such a sewing and knitting in an act of defiance against a deeply patriarchal political system.

There is so much to say about the colour pink, and these thoughts and ideas are merely a fraction of what the colour pink means to people living in the 21st century. For this year’s presentation at FNB Art Joburg, Everard Read would like to present PINK, a small collection of artworks responding to the colour pink. We have selected a small group of artists to participate, each artist has either referenced the colour or ideas related to this colour in their work, and have something to add to the conversation around such a complex shade of red.