PRESS RELEASE

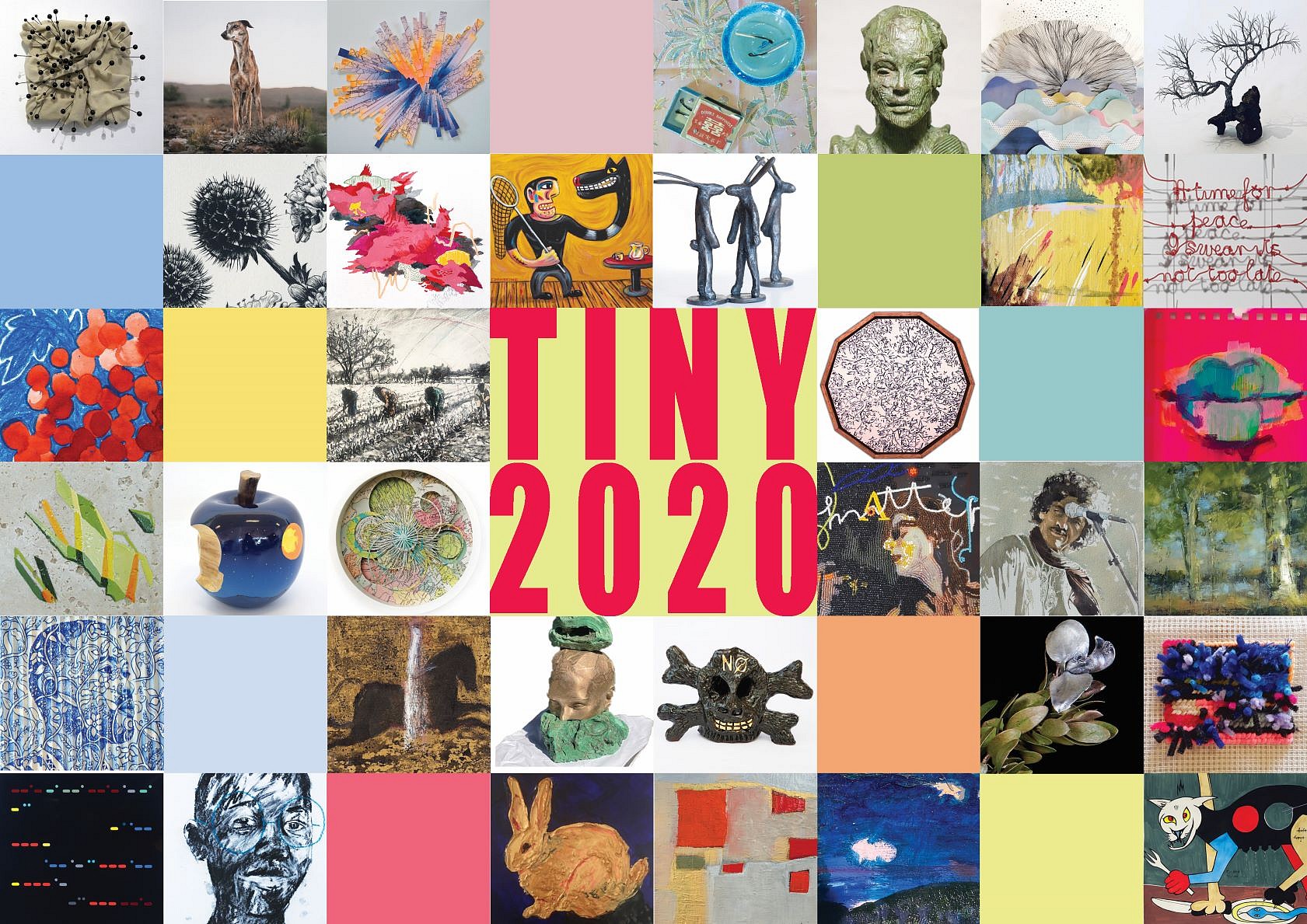

GROUP EXHIBITION: TINY2020

Jul 21 – Sep 9, 2020

In a world obsessed with growth, largely fuelled by the tenets of Western capitalism where “bigger is better” - we had forgotten the importance of the small, the tiny.

In March 2020, people across the world were encouraged to stay at home, limit their exposure to society and thus curb the spread of Covid-19. For the first time in years, people were forced to engage with the interiors of their homes, reckon with their home’s shortcomings or relish the comforts. Suddenly our focus shifted away from the grand, the long-term, the unnecessary, and, instead, we were able to consider the details, the basic necessities, the little things.

This microscopic virus has held the world hostage for months, threatening millions of lives and crippling economies - terrorising humankind and yet too small to see with the human eye.

This point did not escape the notice of artists, whose practice was also interrupted by the pandemic, neither did the major political and social movements catalysed by the tragic and brutal death of George Floyd in America.

Sanell Aggenbach felt this keenly, “If 2020 has taught us anything, it’s the power of the seemingly small and insignificant. Covid-19 has bought us to our knees, one man’s death at the hands of Police brutality in the US has ignited a global movement. Our respect and recognition of these singular and small moments and viruses has forced us to re-evaluate who we are and what’s important not only to our lives, but the world as a whole.”

Wayne Barker, a seasoned commentator on social upheaval, shifted his focus away from his searingly critical, broader observations of society at large, and painted portraits of the people around him: loved ones, friends, friends of friends, sent the artist selfies taken with their smart phones as the starting point for the portrait. The portraits speak to the private moments, the refuge taken inside homes, the tenderness of the artist toward his sitters and the loneliness and isolation that has been felt during this time.

As Patricia Fumerton states in her essay "Secret arts: Elizabethan miniatures and sonnets”, Elizabethan miniature portrait paintings were kept in the intimate space of the private bedchamber, whereas the stately, large-scale portrait paintings were displayed in public areas and gallery rooms. She suggests that because of their diminutive scale the artist focused on depicting the face, shoulders and hands of the sitter - the features that convey emotion and feeling. In contrast, the grand, stately portraits would show the sitter in their entirety, sometimes from some distance, in order to include the symbols of power, rank and wealth associated with the subject of such a work. She goes as far as to say that “Miniatures and oil paintings, indeed, were opposed in their very subject… where the oil painting represented “a statesman, a soldier, a court-favourite in all his regalia,” the miniature showed “a lover, a mistress, a wife, an intimate friend.”

It is interesting that Barker pivoted inward toward the personal, toward the people close to him, physically and figuratively.

Fumerton also points out that with the diminutive size of the Elizabethan miniature, the viewer had to examine the artwork closely in order to appreciate its skill, and the act of showing the artwork to another was a physically close exchange of a deeply personal nature - made even more intimate by the private nature of the rooms in which these pieces would be kept.

The way we engage with small artworks is certainly different to the way we engage with works of a larger scale. The rat sculptures by Lucinda Mudge urge the viewer to come in closer, she explains that “the closer you get the more detail - gold text and images will become visible”, as will “tiny gold fingernails, tiny ratty tattoos, tiny ratty teeth - a tiny rat holding a tiny baby rat, both crying!”.

Elizabethan miniatures were so small that they were also worn as ornaments, around necks, wrists and pinned onto bodices. Marianne Koos describes them as “highly mobile, migrating things that can be acquired and given, accepted or refused, worn on one’s own body or passed on and circulated, thereby establishing social and economic networks.”2

The portable, tactile quality of miniatures is particularly evident in the sculpture of Wilma Cruise, whose works cry out to be picked up and handled. As do the gestural fingermarks in Dylan Lewis’s beasts, which allow the viewer to trace the artist’s method of gauging and scratching into the clay with his bare hands.

The skill necessary to produce a small artwork, to execute the level of detail expected by a viewer engaging with the artwork up-close, is a mastery some artists have practiced their entire careers to achieve.

The phenomenon of miniature painting is not exclusively European, it has been practiced by societies around the world for centuries. One example is the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). During this period, miniature painting flourished, initially practiced to illuminate and illustrate manuscripts, often reflecting the personal interests of the patron commissioning the manuscript. The style changed in the eighteenth century, reflecting the European influence in the region and the demand for portraiture grew.3

To this day, miniature painting is a point of national pride in Pakistan, and a four year degree in Miniature Painting is currently taught at the National College of Arts in Lahore. As a component of this course, “students learn the miniature tradition of making a brush from the hair of a squirrel’s tail which is inserted into a pigeon quill and then attached to a bamboo or reed handle…The miniature technique is a laborious and precise one. Students must first perfect drawing lines in black ink with a single-strand squirrel hairbrush before they can move on. Once they have mastered this they learn rungamezi or filling in the colours. All this is done in minute feather light strokes known as pardokht - a technique similar to pointillism but requiring much more finesse and control and probably the most important aesthetic of miniature painting.“4

This minute level of detail is evident in the highly-detailed botanical sculptures of Nic Bladen. Bladen has refined his casting technique to that he can perfectly render the delicate veins of leaf in metal. The effect is nothing short of astonishing. Johan Stegmann takes his practice beyond the minute and into the microscopic, literally. His etching is fully visible through the lens of a microscope (displayed with the artwork), the technique and level of skill required to render an etching so tiny, is indisputably comparable to the use of a single-stranded squirrel hair brush.

Another artist utilising the etching plate is Jane Eppel. Known for her extremely detailed etchings, Eppel has produced a series of works depicting the long stems of flowers as though viewed from amongst them. Conjuring the fairytale of Thumbelina, the viewer feels as though they are the size of a thumb, standing within the work and looking up at the towering flowers.

Blessing Ngobeni, well-known for his complex collaged works on canvas, created a series of acrylic paintings on paper for this exhibition. In contrast to some of the highly-detailed works featured, Ngobeni found himself simplifying and editing his practice - initially due to a lack of access to materials and to his large studio during the strictest period of the lockdown in South Africa, but he also appreciated the intensity and clarity of these images. He explained that “Sometimes you have to squeeze big ideas onto a small surface, so it was like unpacking, and painting details, and stripping down the large idea into smaller pieces.”.

As Claude Levi-Strauss once said, “being smaller, the object as a whole seems less formidable. By being quantitatively diminished, it seems to us qualitatively simplified”5. This simplicity can be a refreshing, respite from the madness of the anthropocene. Ricky Burnett’s paintings may be small, but capture the quiet hum of stillness - a sound rarely experienced in the 21st century.

Bachelard Gaston, in his seminal tome “The Poetics of Space”, tells an evocative tale illustrating the power of fantasy - by allowing oneself to inhabit the world of the miniature. He explains, “If need be, mere absurdity can be a source of freedom”6; this concept perfectly captures the power of Norman Catherine’s small paintings and sculptures, the magic in their absurdity.

Gaston concludes, “Thus the minuscule, a narrow gate, opens up an entire world. The details of a thing can be the sign of a new world which, like all worlds, contains the attributes of greatness. Miniature is one of the refuges of greatness.”.7 This could not be more true of the works by artists Barbara Wildenboer and Beth-Diane Armstrong. Wildenboer has created wondrous orbs, from delicately cut paper suggesting universes within universes, and Armstrong had created a tree from knotting thousands of steel threads into completely unique forms, resonating and amplifying the organic energy of a real tree and the power of nature.

The 21st century may be an unprecedented age of technological advancement, but, as Beezy Bailey points out, we view art and our surroundings through the ancient format of the miniature on our cellphone screens daily. “What I find interesting in today's world is how a 4sqm painting is reduced to the size of a matchbox on our Instagram and that is how a lot of people see the finished work… So the small scale painting becomes more like the IG image.”

The curatorial shift toward the diminutive is not the first of its kind - but it is a historical moment for the Everard Read gallery in Johannesburg which, as an institution, has championed the production of monumental sculpture by contemporary South African artists. The CIRCA gallery was purpose-built to showcase immense pieces of sculpture and, since its construction in 2009, has housed exhibitions of monumental bronzes by like likes of Norman Catherine, Deborah Bell and Lionel Smit, to name but a few. In direct contrast to these historic exhibitions, Norman Catherine, Lionel Smit and Deborah Bell have created tiny art works for this exhibition, and the contextual shift allows for an altered, perhaps more fantastical reading of their work.

The “new world” opened by the exploration of the miniature is experience by both the viewer and the artist. Lady Skollie mused that “Working small is the gateway drug of going big… A small focus point can make the mind think bigger and that is what I enjoy about working small.” Fred Clarke has also created works that are filled with colour and detail, applied in repetitive and automatic motions to create complex, organic forms.

Deborah Bell uses elements of meditation in her practice, accessing an expansive spiritual realm through intense focus. Reducing the size of the work, Bell taps into an ancient use of transformation in scale to create a magical realm. As Hung Wu explains,“Stories of miniatures, not just in China but worldwide, often involve an imagined process of shrinking, in which a subject or object is reduced in size without altering its intrinsic appearance and proportions. As a magical happening, such transformation provides a useful means to frame a fictional space and to initiate a fantastic journey.”8

Rina Stutzer’s Stealing the Hole in the Sky references the “fantastic journey” undertaken by the crow in Ted Hughes’s poem, Crow’s Fall, and the creation myth of the world being accidentally created as a result of the failed trickery attempted by the bird. The small work, made of cast bronze, captures the chaos of the bird, falling through the universe (signified by the polished bronze ring) in the moment the world is created. Such a small object, yet its diminutive size captures the magic of this moment.

The exhibiton will open online on the 21st of July 2020.

Click here to be request an exhibition portfolio.

PARTICIPATING ARTISTS INCLUDE

Angus Taylor, Barbara Wildenboer, Beezy Bailey, Beth Diane Armstrong, Blessing Ngobeni,

Brett Murray, Bronwen Findlay, Bronwyn Lace, Caryn Scrimgeour, Chonat Getz,

Colbert Mashile, Daniel Naude, Deborah Bell, Dylan Lewis, Fred Clarke, Gary Stephens,

Guy du Toit, Heather Gourlay-Conyngham, Jane Eppel, Johan Stegmann, Jordan Sweke,

Justin Southey, Keneilwe Mokoena, Kilmany-Jo Liversage, Lady Skollie, Leigh Voigt,

Liberty Battson, Lionel Smit, Liza Grobler, Lucinda Mudge, Lyndi Sales, Matthew Hindley,

Michael MacGarry, Nandipha Mntambo, Neill Wright, Nelson Makamo, Nic Bladen,

Nicola Taylor, Norman Catherine, Paula Louw, Pauline Gutter, Penelope Stutterheime,

Philippe Uzac, Phillemon Hlungwani, Rebecca Haysom, Richard Penn, Ricky Burnett,

Rina Stutzer, Sanell Aggenbach, Setlamorago Mashilo , Tamlin Blake, Walter Voigt,

Wayne Barker, Wilma Cruise.

REFERENCES

Fumerton, Patricia, (1991) "Secret arts: Elizabethan miniatures and sonnets", Fumerton, Patricia, Cultural aesthetics: Renaissance literature and the practice of social ornament, 67-110, University of Chicago Press. (p.70)

2Marianne Koos (2014), “Wandering Things. Agency and Embodiment in Late Sixteenth-Century English Miniature Portraits”, Art History 37 (2014), H. 5, S. 836-859.

3 Durriya Dohadwala, (2013), “Reviving Tradition - Pakistan’s Contemporary Miniature Art”, PASSAGE March / April. p.21

4 Durriya Dohadwala, (2013), “THE AGENCY OF INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITIONS AND CURATORIAL PROJECTS IN THE POSITIONING OF PAKISTAN’S CONTEMPORARY MINIATURE ART”, LASALLE College of the Arts. p.7

5 Leìvi-Strauss, C. (1962) La penseìe sauvage, Paris: Plon. p.23

6 Bachelard Gaston, (1994), “The Poetics of Space”, Beacon Press. First published 1958. p.150

7Bachelard Gaston, (1994), “The Poetics of Space”, Beacon Press. First published 1958. p.155

8Wu Hung, (2015), “The Invisible Miniature: Framing the Soul in Chinese Art and Architecture”, Association of Art Historians. p.288.